The month of April could be a harrowing one for the American health system. As COVID-19 approaches, it’s a certainty that ICU capacity will be strained in many regions of the country.

It’s already begun in New York City, Seattle, New Orleans and elsewhere—not to mention what’s been going on overseas. Health care CEOs are scrambling to figure out how to increase intensive care unit (ICU) capacity and take care of a flood of COVID-19 patients—whether it’s using internal or external resources as well as traditional and non-traditional methods. Hospitals and health systems are moving around resources to become ICU-centric.

“The biggest shift we’re seeing is health systems beginning to transform their facilities to become ICUs,” says Roy Schoenberg, MD, President and CEO of Amwell, a telehealth company with customers in all 50 U.S. states. “I can’t think of any health system that we serve that is not in some shape of form jumping into this COVID-19 fight. They all got the messaging.”

Here are six ways health care stakeholders are expanding ICU capacity to deal with COVID-19.

Canceling elective surgeries and non-essential care/repurposing other hospital units

This is a step that most health care providers have already taken, although not all have made that choice. It’s even been mandated by state governments in some areas. While elective surgeries provide a significant revenue stream for health care systems, CEOs have recognized those beds are needed to deal with critical COVID-19 patients.

“Every organization across the country should be eliminating non-essential activity—in any industry, including health care,” says Lou Shapiro, CEO of Hospital for Special Surgery, a provider in NYC that stopped doing non-essential services to help local organizations deal with the flood of coronavirus patients. “Based on our principles, it was an easy decision to [cancel elective surgeries and non-essential care]. We don’t have people coming in that could infect staff. We don’t have people coming in who will take staff away from other important work. It contributes to social distancing.”

Using ambulatory surgical centers

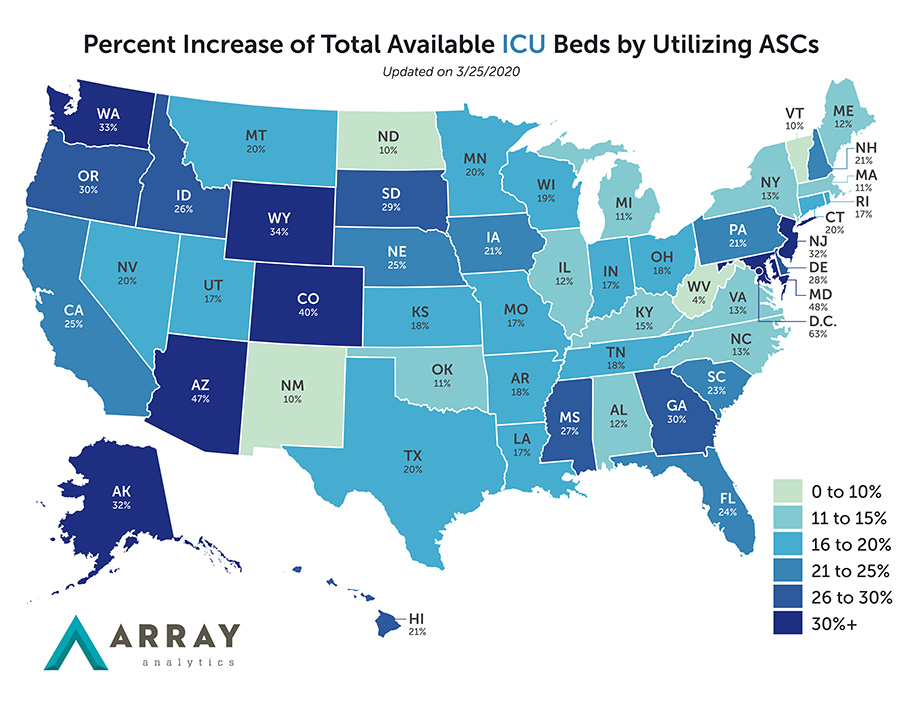

These centers could increase ICU capacity by as much as 60 percent in some states and regions (see above graph), according to new data from Array Analytics. Array’s founder and president Fady Barmada says that ambulatory surgical centers (ASC) provide an overflow opportunity. They can provide facilities for clinicians to care for essential non-elective, acute-care medical patients, reserve resources and protect frontline caregivers.

But even under these circumstances, Barmada says ICUs will get overrun with COVID-19 patients. Thus, Array looked at what could equate to ICU and a med surge bed in an ASC—from an equipment and a space standpoint. Using the Hospital Referral Region (HRR) and state analyses on disease progression, their model projects that employing ASCs will increase the national potential ICU bed supply by 21 percent and med-surg bed supply by 8 percent. In states like Arizona and Maryland, it’s nearly 50 percent. In D.C., it could increase ICU bed supply by 60 percent.

“ASCs offer a potential along multiple strategies,” Barmada says. “Health systems, state governments—everybody is scrambling to look for places to operationalize assets to potentially help with housing these cases.”

Work to convert hotels, convention centers and dorms

This is where health care organizations and state governments are getting creative. In some cities, such as Chicago and NYC, hotels are being converted into makeshift ICUs. Array calculated hotel availability in terms of housing ICU patients across the country. That data can be found here.

“Hotels are one of the major assets everyone is looking at right now. There are 5.4 million hotel rooms in the U.S. A lot are clustered around areas that are the hardest hit right now. They offer a significant value,” says Barmada.

It’s not just hotels though. Convention centers, like Javits Convention Center in NYC and the convention centers in Atlantic City and New Orleans, are being transformed into makeshift hospitals. Dorm buildings are also being considered for hospital overflow in many regions of the country. Health systems and trauma centers in those cities are collaborating to send COVID-19 patients to the appropriate setting.

Collaborate with other health systems and local officials

Speaking of cross-regional collaboration, health systems in cities like NYC, New Orleans, Portland and elsewhere are operating as a cohesive unit to deal with COVID-19 patients. This collaboration can help allocate resources more effectively. For instance, HSS in NYC is taking in urgent, non-COVID patients from Weill Cornell and NewYork-Presbyterian hospitals. Washington state-based Providence St. Joseph Health (PSJH) is using its capabilities in AI and virtual health to spread the wealth across the region and the country.

Read more: Health care executives put aside competitive differences to fight back COVID-19

Health care organizations are also increasingly collaborating with local officials to create a uniform triage strategy. In some cities, triage tents have been set up, according to CDC and local guidelines, to prevent people from going straight to the emergency room.

Virtual care

Like PSJH, health care organizations across the country are relying on virtual care environments to treat routine and non-essential care. In the past month, thanks to emergency rules from CMS and waivers from other payers, telemedicine usage has surged in various parts of the country. According to Kaiser Health News, The Cleveland Clinic is on track to log more than 60,000 telemedicine visits in March. Before that the health system had about 3,400 per month. PSJH said they saw a significant jump in usage of telemedicine during the first week of the crisis alone.

Some hospitals are taking virtual care even further. Atrium Health in Charlotte, N.C. has launched a virtual hospital where they will monitor patients who tested positive for COVID-19 but don’t need intensive care. Each patient receives a monitoring kit, which includes a blood pressure cuff, pulse oximeter and thermometer.

“This is a safe way to care for the appropriate patients at home and is comparable to what they would receive in the hospital,” Scott Rissmiller, MD, chief physician executive at Atrium, said to the Charlotte Business Journal.

Modular hospitals

If you can’t find the space for ICU beds, why not build it—or find one that’s prebuilt? Barmada of Array said the idea of modular care (or pre-fabricated) units is being developed by several firms. Volumetric Building Companies in Philadelphia, for example, is working with factory industry partners to retool efforts and create these modular units in 2-3 weeks. The company says its units can provide immediate needs for triage, quarantine, patient recovery, and care staff resting quarters, and they can be moved quickly from city to city. Other companies are similarly working on these kinds of designs as well.

“Health systems are going to have to figure out how best to operationalize and use them. There’s a lot of opportunities for them, but [health care CEOs] will have to figure out how deploy them and use them,” Barmada says. The units provide space and capabilities to health systems to expand their operational options and create opportunities for them to ultimately weather this storm.”