When it comes to an impact on health care settings, the COVID-19 crisis hasn’t been limited to hospital intensive care units (ICUs). It has devastated the outpatient world as well, albeit in a different way.

In the month of April, researchers from Harvard Medical School revealed that the number of visits to ambulatory practices declined nearly 60 percent. And while the number rebounded in May, it still remains much lower than what it was before the pandemic.

One of the hardest areas hit by this drop off was primary care. According to the research, primary care saw a 51 percent decline in April compared to a baseline in early March—by May, it still had a 25 percent drop off. In some places, such as New York City, primary care physicians saw up to an 80 percent decline in visits.

The financial aspect of COVID-19 has hit small, independent primary care practices (nearly half of all primary care docs are independent) very hard, in particular. Nearly half of primary care physicians, according to one study of doctors in smaller practices, had to lay off or furlough staff. Nearly 70 percent expressed a growing and extreme sense of financial and emotional strain. Even with potential advances in payment from CMS and other payers, experts say many practices will be forced to close without sufficient earnings and revenue. Some practices have already had temporary and permanent closures.

Practice closures mean reduced access to care, and in some communities, these providers are the lifeblood of the community. Lower access to care means worse outcomes and increased costs. However, COVID-19 has given health care organizations the opportunity to re-emphasize primary care as the centerpiece of patient-centered model of care.

What will be the full impact of COVID-19 on primary care? And what opportunities will emerge to create a stronger primary care system? In a two-part series, Health Evolution interviewed a panel of experts on the struggles of primary care during COVID-19 and the potential positives that could come out of this pandemic. Below is part one of this series.

Panel of experts:

Farzad Mostashari, MD, CEO of Aledade, which partners with independent practices, health centers, and clinics to build and lead Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs); former National Coordinator for Health IT

Ateev Mehrotra, MD, associate professor of health care policy and medicine at Harvard Medical School

Christine Bechtel, president and chief strategist, X4 Health, a strategy consultant firm

Scott Shreeve, MD, CEO of Crossover Health, a digital health, national medical group

Chris Koller, Milbank Memorial Fund, an operating foundation that works to improve population health; former Health Insurance Commissioner of Rhode Island

What kind of strains has COVID-19 put on primary care?

Mostashari: The first strain is being able to respond to it while protecting their patients and staff members. We’re all taking extraordinary precaution for ourselves and staying in isolation. These primary care practices are essential workers—these doctors and nurses are sitting in a room and waiting for patients to come in with cough and fever-like symptoms. And then they close the door. Day after day. Patient after patient. We saw a surge across the country in March/April of a higher rate of patients coming in with fever and cough, and it turns out a lot of those people had COVID.

And yet these heroic practices have taken care of them, even with the absence of PPE. We literally had doctors using scotch tape to tape surgical masks to their faces because they couldn’t find N95 masks. We’ve had staff members die of COVID. Office workers. Practice workers. We’ve had physicians in our network who have been hospitalized, who have had their spouses hospitalized. We hear a lot about hospital workers as being the heroes here. Primary care is no less heroic and no less on the front lines. As usual they don’t get the credit. Why should this time be any different?

Shreeve: Primary care has been caught flat footed. A lot of these practices that on the fee-for-service, visit-based model are really struggling. That’s unfortunate because this is the time where good solid primary care should be having an impact, making sure patients at risk are kept safe and those who have needs are being addressed through virtual technology or otherwise. While that should be the case and primary care should have this really important role, given the financial model, they can’t be effective. So now all these primary care docs who don’t have ability to switch to virtual are having these challenges. I think it’s unfortunate. The infrastructure doesn’t allow primary care to have the impact it should.

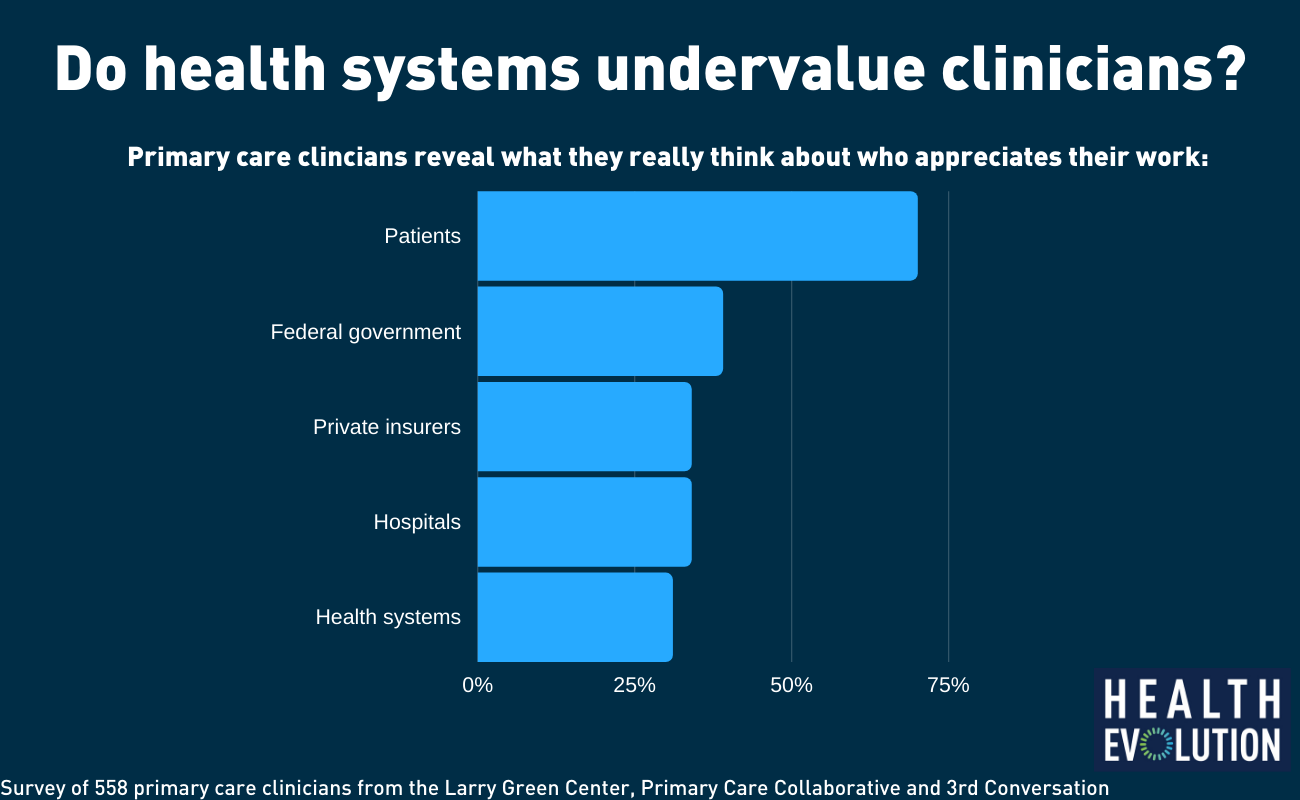

A recent survey reveals the disconnect between how primary care clinicians perceive their patients value them and their work and how major players in the health care system value them and their work

Bechtel: The strain is in four different areas. The first is financial, which is probably the most dramatic area. We’re learning from the Green Center survey data that about 50 percent of primary care practices have had to lay off or furlough their staff. At the same time, about 15 percent of primary care practices have temporarily closed. Another 40-45 percent aren’t sure they’ll be open in four weeks. It’s hard to imagine how all of this is happening in the middle of a pandemic, when we need primary care the most.

Second, week over week, consistently half of practices still have very limited access to testing and more than half have no PPE to protect them. That’s a major issue because we’re counting on primary care to feed data back to public health departments to measure community spread. If we don’t have testing, if we don’t have PPE and we’re closing our doors, that’s not going to work out well for the public or for our economy.

Two other issues of great concern – the general wellbeing of people who are on frontlines of primary care, and patients worrying about losing their doctors. Surveys are showing rising rates of burnout. Three quarters of practices are operating under severe or near severe stress. They are feeling uncared for, especially by insurance companies and policymakers. What’s more is that two-thirds of patients say they would be “panicked, heartbroken or upset” to lose their primary care doctor. So, there’s a big threat to the continued existence primary care right now, and patients (read: voters) want to be sure their doctors will still be there for them.

AMA’s Patrice Harris on health care’s double crisis: COVID-19 and clinician burnout