By now, the evidence should be clear to everyone. Vaccines work.

Kaiser Family Foundation recently analyzed data from more than 20 states comparing recent COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations, and deaths among the vaccinated and unvaccinated. In every state KFF analyzed, unvaccinated people accounted for no less than 94 percent of the cases. Most states only saw 0-2 percent of COVID-19 cases and hospitalizations coming from vaccinated breakthroughs. For deaths, it was an even smaller percentage. Among those who are not fully vaccinated, the death rates from COVID-19 ranged from to 96.91 percent in Montana to 99.91 percent in New Jersey.

The CDC released even more telling numbers: Of the 163 million people fully vaccinated in the United States against COVID-19, 6,239 were hospitalized, 26 percent of which reported as asymptomatic or not related to COVID-19.

This makes it more imperative that health care leaders continue to implement strategies to improve vaccination rates. Overall, the U.S. surpassed 70 percent for partially vaccinating adults 18 and over, though not by the Biden administration’s stated goal of July 4. CDC also data found that certain demographics are lagging.

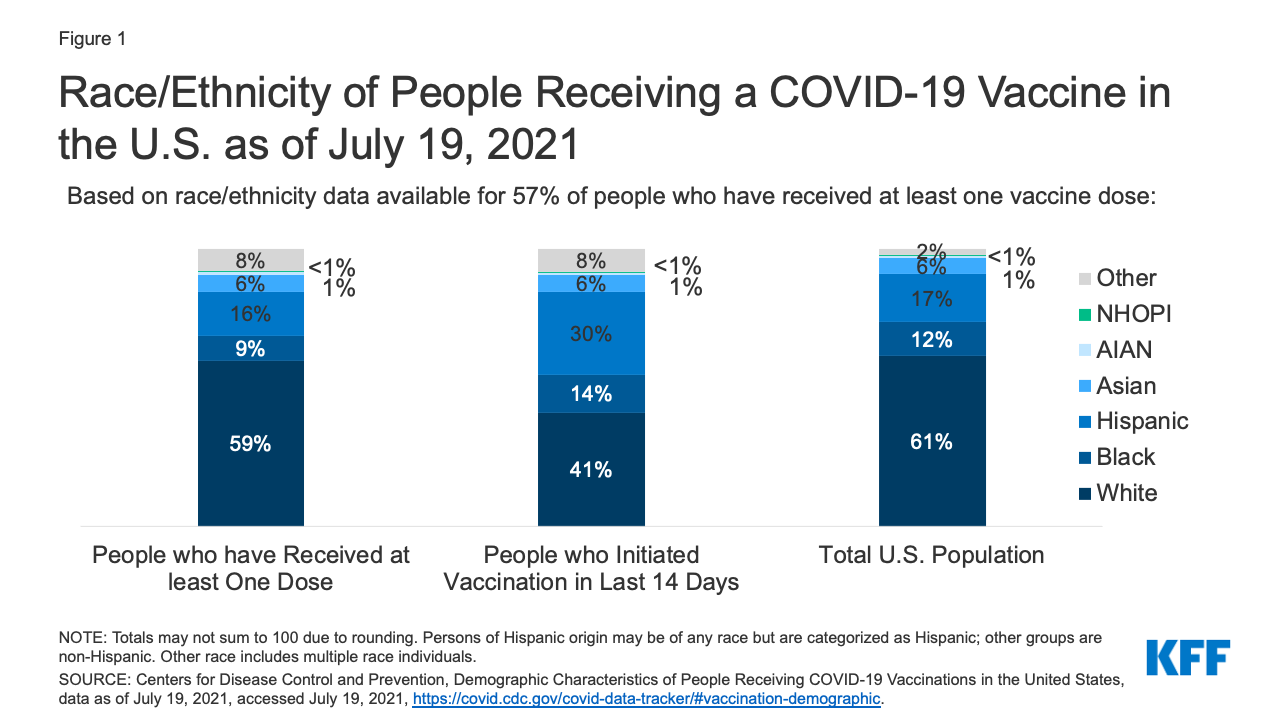

Of the most recent demographic data available for those who were vaccinated at least once, nearly two thirds of the people were White (59 percent), 9 percent were Black, 16 percent were Hispanic, 6 percent were Asian, 1 percent were American Indian or Alaska Native, less than 1 percent were Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, and 8 percent reported multiple or other race. In the last 30 days, however, 30 percent of those vaccinated were Hispanic, 14 percent were Black and 6 percent were Asian Americans. Yet, as of July 19, KFF reported that fewer than half of Black and Hispanic people have received at least one dose of the vaccine in every single state that has reported data.

A guide from the Health Evolution Forum Fellows on the Roundtable on Community Health and Advancing Health Equity: Increasing Vaccine Uptake in Diverse Communities, created in partnership with Change Healthcare

A new report from researchers at UCSF published in JAMA found that improving vaccine equity means that “systems administering vaccines must be ready to reach historically marginalized populations to ensure equitable access.” The researchers break down equitable access into three categories: high-barrier, intermediate-barrier, and low-barrier systems.

Those with low-barrier systems not only have mass vaccination sites and online scheduling, but they also offer pop-up vaccine sites in the community, pay attention to language access for people with limited English proficiency and provide some navigation using telephone, text messaging, and in-person outreach. Safe transportation is also provided in a low-barrier system.

The researchers said that San Francisco Health Network pivoted from online vaccination scheduling because it was preferentially attracting tech-savvy upper-income White residents rather than the organization’s traditional patient population, which mostly comprises lower income individuals and Asian, Black, and Hispanic individuals.

Partnerships work

These kinds of low-barrier systems are adept at partnering with community-based organizations, experts say. This has been successful in improving vaccine rates in Arkansas, says Creshelle Nash, MD, Medical Director for Public Programs and Utilization Management at Arkansas Blue Cross Blue Shield.

“A top-down approach doesn’t work in my experience. We have to realize that local people and local leaders are experts in their community. And we have to understand local communities to have an impact. We cannot assume that a one-sized-fits all strategy works. In our community engagement model, we are working with the existing organizations that are trusted in their communities,” Nash said to Health Evolution.

One state that has seen success in vaccine equity is North Carolina. From December of last year to April 2021, the proportion of vaccines being distributed to Black North Carolinians increased from 9 percent to 19 percent and the proportion going to Hispanic North Carolinians increased from 4 percent to 10 percent. This closed the gap for the 22 percent of the state’s Black residents and 9 percent of its Hispanic residents. Partnerships between vaccine providers and community and faith-based organizations, with focus on communication activities and toolkits, was a major strategic initiative that helped boost these numbers.

“We’ve built equity into every aspect of our vaccine distribution. Our commitment to equitable vaccine distribution is one piece of our continued work to address and dismantle systemic and structural barriers to health equity,” said Mandy Cohen, MD Secretary of the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services. Cohen is also a member of the Health Evolution leadership committee.

Health systems need to not just improve access, but continuously educate and communicate with “multidimensional outreach programs,” according to the UCSF researchers. This can help improve vaccination rates among those who are skeptical or want more information.

Likewise, the researchers suggested not using the word “vaccine hesitancy,” an idea that was espoused by Nash. “I would call it something much stronger than hesitancy. It’s actually a mistrust of the health care system. There is a mountain of evidence in the literature that suggests communities of color don’t have access to quality health care,” Nash said.

Homepage image: Jakayla Toney/unsplash